Race and culture in theatre is something that I have been aware of from a very young age. When I first started doing youth theatre workshops, I was often one of very few white participants (and, even then, I’m mixed White/Caribbean). But what I have found peculiar, is that only a small percentage of black young people have come through into the industry as professional creatives. Acting seems like the common ground.

There are so many aspects of race to discuss, so this could be considered an introduction to a topic I shall probably return to.

Jade Lewis is a director and playwright. Most notably, she was Trainee Assistant Director on Blackta by Nathaniel Martello-White which premiered at the Young Vic in October 2012 directed by David Lan. Eric Abrefa is an actor. In September 2012 he took to the Royal Court stage as Bobby in Choir Boy by Tarrell Alvin McCraney, directed by Dominic Cook.

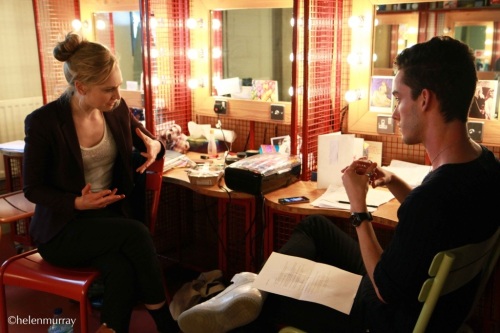

I meet Jade and Eric early at the Young Vic (where else?) and over a tea we begin to talk…

I suppose the best place to start is to ask how and at what age you both got into theatre?

Eric: Around 15. I had just started GCSE Drama and we did Richard III at the Pleasance Theatre in a BBC Shakespeare festival and I had the opportunity to play Richard and it was just amazing. It was the first time that I’d been on stage and the buzz from that was incredible and I thought ‘This is definitely what I want to do; I want to feel this buzz all the time’. After secondary school I went to Brit School and then drama school.

Jade: Yeah, I’m similar to Eric in that I started with GCSE drama then went to college and did Performance Studies and joined a production company called Mayhem and began acting with them. I got to the end of college and I realised that I wanted to do something in theatre but I didn’t want to perform. I enjoyed performing, but I’d rather let someone who’s better than me do it. Not saying that I wasn’t good – you know? I’d just prefer to see the whole picture rather than me within it. I went to university and studied History – something completely different – but it was something that I enjoyed and loved and that I could use regardless of what I did after. After that I just got into directing.

Are you the first generation in your family to go into something creative?

Eric: Oh, yeah, yeah… my uncle who was a bus driver – I think he still is – …I had just got my acceptance letter into Royal Welsh College and I literally had it with me, going on the bus, and he saw me and he was like, ‘How you doing?’, ‘I’m fine’, he was like ‘I hope you’re not still doing that acting stuff‘, and I just looked at my letter and was like, ‘Nah, no, I’m just going to college now’. Yeah, so I’m the first and hopefully not the last.

How was that received? Were you expected to do something more academic?

Eric: My mum is first generation Ghanaian who came to this country and I’m the first-born here and the culture there is obviously different; they’ve come here to seek greener pastures and, you know, they want you to be the best you can possibly be. They didn’t make that journey for no reason. They want you to be a lawyer, a doctor, something that can bring in money and constant employment. I suppose, they didn’t see it as a good choice of work. My mum never went to university and I had never been, it was us together: ‘Whatever you want to do, do it, but do it to the best of your ability and make me proud.’ I couldn’t settle for a better deal.

What about you, Jade? [All of the above]

Jade: I am the first to get into something creative. I was also the first to go to university. When I said that I wanted to go into theatre, they were like: ‘Whoa, you should be doing a Masters!’ My uncle said: ‘You should write books’ and I was like, ‘No, I’m going to write plays.’ It was a big stand-off. My mum told me to do what I wanted to do, that I’d be good at it anyway. She’s always been supportive like that, and I haven’t really cared what other people have thought because she’s always had my back. She’s one of those mothers – as scary and as hard as she is – she cries when she sees me on stage. She says, ‘You know I can’t come and see your performance, I’ll cry!’ So she never saw anything I did.

In regards to shows that you’ve been involved with – mainly Choir Boy and Blackta – did you feel as though they were stand-out shows because they were an all-black cast?

Eric: What I loved about it was that Tarrell [Alvin McCraney] used five black African-American boys who were in a prep school; so they’re bred and taught to be the leaders of tomorrow and that’s not usual when it comes to anything “black”; there’s usually a stereotype of someone getting stabbed, shot or killed. These boys were the bright boys, so in their society they’re going to make a change, they’re going to be the bankers, the big things that people aspire to be; but within that, they still have their issues and it still had really challenging themes. In theatre, the best thing I’ve enjoyed is tackling strong themes and issues and moral questions and judgements. What is the point in seeing something that you know about already? So, with Choir Boy, I felt it stood out because of how the audience received it. The protagonist, Pharus, was born to be a leader and he’s born to be the leader of this choir, but the thing was that he was gay and that was the issue and how everybody else received it. His best friend, AJ, was cool with it, my character wasn’t so cool with it… So, it was like, ‘Lets see how that plays out’ and I felt that was amazing, rather than, you know, having a play about boys on the street and you can see where that is going. When it comes to “black” theatre, we need things that will challenge us more.

In terms of tackling stereotypes in theatre, Blackta…

Jade: You know, it’s funny because different nights I saw different messages. Sometimes you’d really see the fact that all of these guys are talented and they want to do well and you see the stresses that they have on their backs, not just because they’re black actors, but the profession, how hard it is to get a job regardless of your age or ethnicity, etcetera. With Blackta, I feel there were a lot of issues they were tackling within the piece. These guys aren’t just black actors, they’re people as well and you hear about their family issues outside of this ‘thing’, but at the same time they never leave this ‘thing’ because that is their life, it’s what they live for and I feel that resonates with creative’s and artists because we all want to do what we are passionate about. It’s inspiring to see people who you can relate to because of their passion and their drive, not just because of how they look. I agree with Eric in the sense that it’s not just about urban dramas. Why can’t it just be a simple story where things just happen and it so happens that these people are of a certain culture? To see how that affects it, or in fact, how similar that is to other cultures that are just seen as… ordinary.

Eric: I feel that as soon as we go down the stereotype route, whether it’s TV or theatre, the characters immediately become 2D, there’re no complexities within them. That’s a great shame because when I’m watching Downtown Abbey, for example, race just goes out the window. I’m looking at a culture, I’m looking at a storyline, people’s journeys through this story and I feel that doesn’t really get to us – we’re getting there – but at the moment we’re not there.

Jade: Sometimes Tom & Jerry is more complex than some stereotyped characters. You can explore a lot with Tom & Jerry or other cartoons. Daffy Duck, there’s so much to him – fair enough, he’s black – but you know what I mean?

Eric, you said ‘We’re not there yet’ – how far do you think we’ve come? Within the last ten years, there’s been a big step. Plays like The Brothers Size, In the Red and Brown Water, Generations – and all of these amazing plays with an all-black cast are coming through and they’re getting onto the main London stages.

Eric: Yeah, they are and it’s great and it’s exciting, but now it’s time to be more consistent. We can count on our hands the writers who are doing this. In Britain I feel the culture is way different. If there is something they don’t know about the culture, they write things on the surface. It’s a shame.

When Feast came up [at the Young Vic, directed by Rufus Norris], I was talking about the potential reviews and someone said: ‘They’ll have to be nice about it, because they won’t understand the cultural references’. So, reviewers have to be nice about certain shows. Is that the world we’re living in?

Jade: Exactly. I know Brits are polite, but that’s taking it a bit too far and, moreover, to be honest, what I think is important as an audience member is that you should get something from anything you see. That is the point of the company, the production – yeah, you want to explore something specific, whether it’s Yoruba culture or whatever, but it’s the fact they’re people and have relationships and there’s an aim to the story – anyone should be able to pick that up. But with the reviews… it’s a bit sad. Just be honest. Even if you don’t get it because it’s different, just say that and maybe ‘I didn’t get it because, dot-dot-dot’. Sometimes difference is good. We’re all different.

Eric: And why are you going to the theatre? Are you going because it’s a cool thing to do, sit down, have a glass of wine and watch actors perform or are you going there to be challenged? That’s what I want to know. I hope you’re going there to be challenged.

Surely, shows about race don’t need to be about a murder or any stereotypes. There are powerful messages behind race and there’s a reason there’s race in this country. That’s what Feast showed.

Eric: Feast was incredible. I loved the personification of the three Gods and how it went through the ages. I thought the themes it tackled were amazing and I just hope things like that can come to the surface even more, you know, rather than watching a piece of theatre to be entertained – that’s great, but there’s a place for that – but don’t expect every type of theatre to be that way.

Photos courtesy of Helen Murray / http://www.helenmurrayphotos.com